While most suburban homes—custom or track—flatten the landscape of the environment into a maze of cookie-cutter residences, the people from Casey Brown Architecture in Sydney, Australia defy both architectural standards and social expectations.

With the intent to create a home that would provide its owners with ample living and working space, as well as embrace the landscape’s natural beauty, principal architect Robert Brown designed a house that endures unusual environmental conditions. Upon first glance, the corrugated copper roofing, the massive glass surfaces and the black-coated steel resemble an organic jewel wedged in the ground.

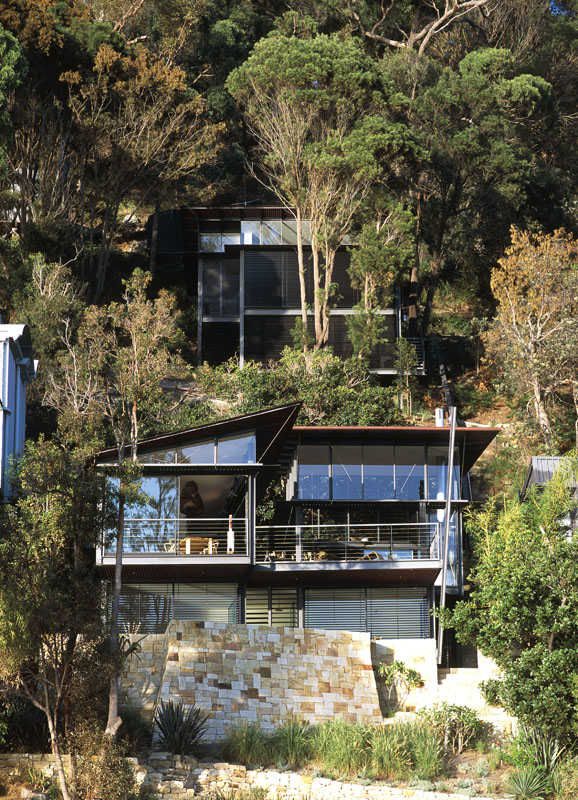

What makes this house particularly unique is that the architect adapted the house to its surroundings, as opposed to changing the landscape to fit the building’s needs. The house sits on a steep 45-degree slope that faces the Great Mackeral Beach in Sydney, and is surrounded by the Ku-ring National Park. In order to reach the home’s entrance, one must take a boat ride and walk along the beach up a hill to the enclosing rampart walls of the entry, which is framed by a Port Jackson Fig Tree. This dense shade tree actually inspired the location of the residence.

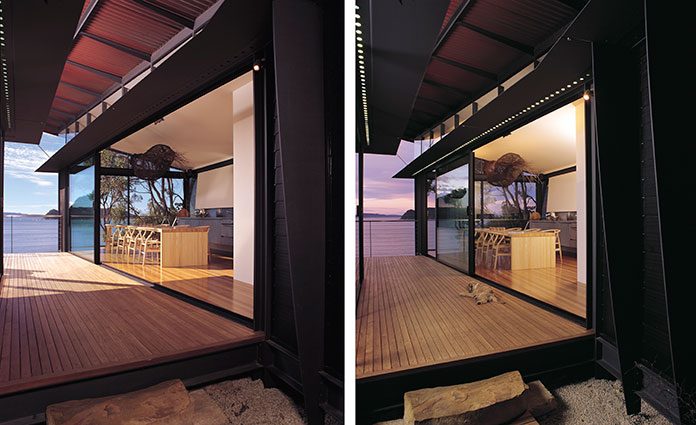

The house itself is divided into three pavilions. The lower two are stabilized by massive sandstone. The walls slope, leading into the first level bamboo grove containing a study, guest room and basement. The first pavilion is intricately linked to the others by the expansive cantilevered floors of the pavilions above. The second pavilion contains a kitchen, dining room and pantry. The transparent glass walls create a wide, open space so the exterior landscape becomes the home’s main décor. The master bedroom pavilion sits 50 meters above the slope and is only accessible by a steep bucket elevator.

When designing the home, the landscape was Brown’s muse. The placement of each pavilion was a response to the steep cliff; and yet, the unconventional decision to comprise a single residence from small, individual structures does not diminish the effect of the home.

In addition to maintaining the integrity of the landscape, Brown designed the home to be environmentally sound and self-sufficient. The structure employs natural resources to maintain itself, including a system to collect and store rainwater, while the home’s design utilizes wind to cool the interior reducing energy. In addition, due to the use of sturdy materials such as copper, steel and glass, maintenance is far less than your typical home.

Designing an appealing permanent residence as well as and environmentally-friendly structure was an important and challenging feat for Brown. “I like architecture that celebrates nature’s extraordinary fecundity and inventiveness, which reminds us that humankind is a part of nature and not separate,” he said.

Because Brown wanted to create a house that was an extension of the earth rather than an entirely separate entity, he never doubted his vision. Whether it meant delivering materials via helicopter or erecting a temporary wharf to bring heavy supplies by barge, he spared nothing to realize his vision.

The success of the James-Robertson project demonstrates that it is indeed very possible to develop beautiful structures without undermining the health and beauty of our environment.